DKA’s recent building experiences have involved off-site building techniques, where modular building components are fabricated off-site, then delivered and assembled on-site. The industry calls this ‘Modern Methods of Construction’ or MMC. We have been assisting The McAvoy Group in developing several such schemes for our commercial and healthcare sectors. The processes and constraints of modular build informs various aspects of the building design, even at early stages. Our recent ventures have prompted some reflection on a building technique which historically has proven to have a strong lure for architects.

Lego of course, in its various guises, would be expected to feature in the formative years of anyone in a career involving construction and architecture. Alongside the obligatory Meccano set, this may go some way to explaining perhaps why modular build, coupled arm in arm with offsite prefabrication and the notion of ‘a kit of parts’ construction, has always held an element of intrigue and seduction for architects and designers. Repetition of simple modular components as means to simplify and shape building design and construction is a thread is woven into the fabric of building history too. Simple components of mud bricks, which could be considered as the most basic building module, dates thousands of years. The humble modern brick still defines standard door and window sizes, even on buildings that feature no brickwork.

Elemental modules are considered by some as the basis of the ‘classical language’ of architecture. In Greek and Roman antiquity, the ‘5 orders’ were considered expression of beauty and harmony based on proportion. A basic unit of measurement was derived from the respective column diameter from which the key elements were dimensioned. Supposedly, Vitruvius described Doric design in modular terms; a module being equal to the triglyph width. This established the lynchpin of a complete modular design system from which the proportion of whole temples were derived. This interpretation helps to explain the consistency of design found in temple facades, particularly apparent from the 5th century onwards. In turn, temple design informed the design pattern for many ancient civic buildings from which classical architecture through its various ages was developed.

Skip forwards in time to the industrial revolution, where the notion of modular building and prefabrication came to the fore. A concept that revolted and attracted The Arts and Craft movement in equal measures. The Crystal Palace in London which housed the Great Exhibition of 1851, is always cited as an important reference point in the development of modular building. It was constructed around the time when assembly lines came into production. Through its accomplished use of prefabricated glass and advancement in structural techniques of ironwork, the building was completed quicker and cheaper than had it been formed in-situ. William Morris was reportedly sick behind a hedge when he visited!

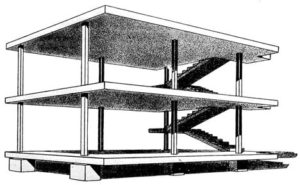

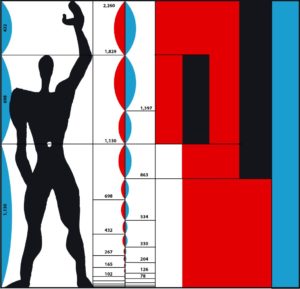

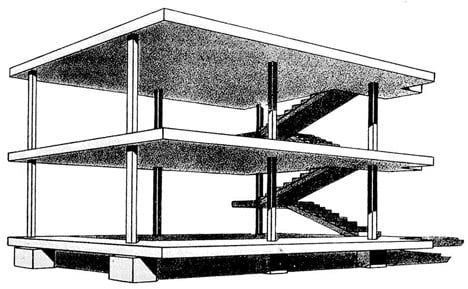

The advent of modernism and the concept of the modular building went hand in hand with the industrialisation of construction techniques and the philosophical ideology that underpinned it. The Modern movement embraced standardisation, systemisation, material honesty and technical innovation. There was a perception that embracing such values would help support social advancement and progress too. Le Corbusier’s 1915 ‘Dom-Ino frame’ was inspired by the automotive industry and development of the Henry Ford assembly line. It is the starting point for a style of design and construction that dominated the 20th Century. Later, his iconic modular man (1943) was inspired by the universal ideas of proportion that were perhaps evident in classical architecture. If buildings are designed for people, why not use the human body as the starting point?

Walter Gropius, an architect with significant academic influence, also put forward ideas of industrial production based on ‘artistically unified principles’. Gropius’s ideas did not really materialise however other than demonstration buildings for exhibitions. R Buckminster Fuller was another notable contributor producing his exemplar Dymaxion House. His response to post-war housing problems utilised the technology of aircraft manufacturing in terms of material and production and process. Again, whilst concept buildings were prototyped and constructed, there was no surge or demand for further production other than isolated instances. Some would suggest that the stalled attempts at the modular building demonstrates it remains as an idealistic and romanticised concept that should perhaps be abandoned. For some the idea of a modular building is not always associated with the convivial.

Since the second world war however, the construction industry has sought to deliver buildings efficiently, economically and effectively. In the U.K. the sometimes maligned ‘prefab’ was only meant to be a stop gap solution to the impending housing crisis after the war. Much loved by many, prefabs are still standing today and even have listed building status in some instances.

There have been recent initiatives centred around offsite construction and ‘smart build’ techniques. There has been a notable drive by the UK Government to incentivise and push forward MMC. Advocates for MMC feel there are many benefits to the system in comparison to conventional site build methods. Modular build should be considered as an economically viable building solution that offers improvement in terms of quality and defective work. It is promoted as having considerable time, environmental, quality and safety advantages when compared to traditional construction. It is however difficult to quantify these, when comparing construction methods, particularly where there are complex variables on large scale projects.

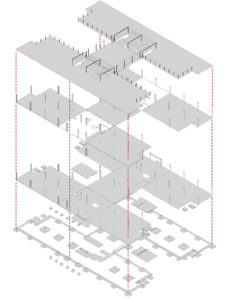

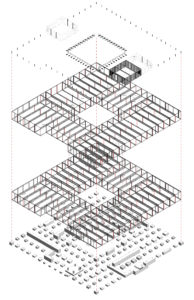

Compare these two diagrams of traditional (left) and modular (right) for two similar DKA-designed buildings on the Porton Science Park site in Wiltshire.

It is also suggested there may be implied wider social benefits to factory-based construction work rather than opportunistic site work. As well as sustainability and safety issues, off-site fabrication may offer equal employment opportunity to a wider spectrum of workers. Work centred on a consistent base like a factory, rather than temporary local building sites, may also present prolonged employment opportunities which can help stabilise communities, particular where production lines are located in populated areas where localised economic difficulties are apparent.

With the present societal challenges, the discussion in support of modular building within the construction industry remains fervent. It continues to be a topical debate and this discussion is likely to continue. For our part, we continue to enjoy the challenge of modular construction, sometimes blending MMC and traditional methods, or existing buildings with modular extensions. Rather than stifling design or creativity, MMC is a new piece of Lego we can utilise as part of an expanding kit of parts.

Very interesting Jon. I hadn’t heard the story of William Morris being sick outside the Crystal Palace, but it could be true! He was acutely uneasy throughout his life of the contradictions between – on the one hand – his championing of hand-crafted objects and processes, and on the other his need to industrialise their production in order to meet demand and make them affordable, even if by the standards of the time his labour relations were very liberal and ‘modern’. He even tried profit-sharing.